We talked not

too long ago about backup withholding.

What is it?

Think Forms

1099 and you are mostly there.

The IRS

wants reporting for many types of payments, such as:

· Interest

· Dividends

· Rents

· Royalties

· Commissions and fees

· Gambling winnings

· Gig income

Reporting requires

an identification number, and the common identification number for an

individual is a social security number.

The IRS

wants to know that whoever is being paid will report the income. The payor starts

the virtuous cycle by reporting the payment to the IRS. It also means that – if

the payee does not provide the payor with an identification number - the payor

is required to withhold and remit taxes on behalf of the payee.

You want to

know how this happens … a lot?

Pay someone

in cash.

There is a

reason you are paying someone in cash, and that reason is that you probably

have no intention of reporting the payment – as a W-2, as a 1099, as anything –

to anyone.

It is all

fun and games until the IRS shows up. Then it can be crippling.

I had the following bright shiny drop into my office recently:

The client

filed the 1099 and also responded to the first IRS notice.

It could

have gone better.

That 24% is

backup withholding, and I am the tax Merlin that is supposed to “take care of”

this. Yay me.

This case was

not too bad, as it involved a single payee.

How did it

happen?

The client issued

a 1099 to someone without including a social security number. They filled-in “do

not know” or “unknown” in the box for the social security number.

Sigh.

Sometimes you

do not know what you do not know.

Here is a

question, and I am being candid: would I send in a 1099 to the IRS if I did not

have the payee’s social security number?

Oh, I understand

the ropes. I am supposed to send a 1099 if I pay someone more than $600 for the

performance of services and yada yada yada. If I don’t, I can be subject to a

failure to file penalty (likely $310). There is also a failure to provide penalty

(likely $310 again). I suppose the IRS could still go after me for the backup

withholding, but that is not a given.

Let me see: looks

like alternative one is a $620 given and alternative two is a $38,245 given.

I am not

saying, I am just saying.

Back to our

bright shiny.

What to do?

I mentioned

that the payment went to one person.

What if we

obtained an affidavit from that person attesting that they reported the payment

on their tax return? Would that get the IRS to back down?

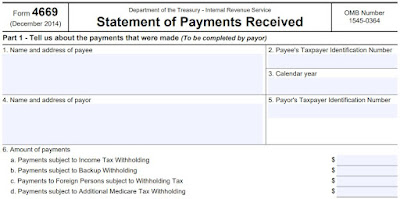

It happens enough that the IRS has a specific form for it.

We filled in

the above form and are having the client send it to the payee. We are

fortunate, as they have a continuing and friendly relationship. She will sign, date,

and return the form. We will then attach a transmittal (Form 4670) and send the

combo to the IRS. The combo is considered a penalty abatement request, and I am

expecting abatement.

Is it a

panacea?

Nope, and it

may not work in many common situations, such as:

(1) One never obtained payee contact information.

(2) A one-off transaction. One did not do

business with the payee either before or since.

(3) The payee moved, and one does not

know how to contact him/her.

(4) There are multiple payees. This could

range from a nightmare to an impossibility.

(5) The payee does not want to help, for whatever

reason.

Is there a

takeaway from this harrowing tale?

Think of

this area of tax as safe:sorry. Obtain identification numbers (think Form W-9)

before cutting someone their first check. ID numbers are not required for

corporations (such as the utility company or Verizon), but one is almost

certainly required for personal services (such as gig work). I suppose it could

get testy if the payee feels strongly about seemingly never-ending tax reporting,

but what are you supposed to do?

Better to

vent that frustration up front rather than receive a backup withholding notice

for $38,245.

And wear out

your CPA.