Can I take advantage of the new tips deduction?

I will be slowing down in 2026: fewer hours, fewer clients, unlikely to accept new clients. It was inevitable, but the events of the last year-plus have accelerated my decision. I was witness to friends and the consequences from their sale of a firm. I do not care to see that again.

Can I do anything in 2026 to catch a tax break?

We are talking about the “No Tax On Tips” provision of the One Big Beautiful Bill signed by the President on July 4, 2025. The break will last four years – beginning in 2025 – and allow a tipped worker to exclude up to $25,000 of “qualified” tips from income taxes.

COMMENT: Yes, the break is retroactive to January 1, 2025 even though the OBBB was not signed until July 4.

COMMENT: The $25 grand is per return. If you file single, the limit is $25 grand. If you file jointly, the limit is again $25 grand. Another important point is that we are talking about federal income taxes only. Those tips are still going to be subject to social security taxes, just like before.

There is an income limit, of course: $150 grand for singles and $300 grand for marrieds.

The break is available whether you are a tipped employee or tipped self-employed. The reporting to you, however, will be different.

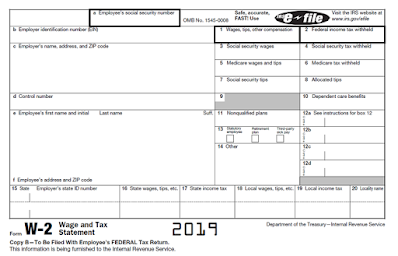

If you are an employee, you will receive a 2025 Form W-2 from your employer.

I want you to notice Box 7: Social Security Tips.

The tips deduction uses the term “qualified” tips.

Mind you, it is possible that Box 7 is also the amount for qualified tips, but it does not have to be. The tax Code does this sleight-of-hand repetitively by sliding the word “qualified” before otherwise innocuous nouns. How can a tip be “nonqualified?” Easy: it is nonvoluntary. How does that happen? Again - easy. Say that you have a party of eight or more and the restaurant applies an automatic gratuity of 18%. That fact that the gratuity/tip is now automatically included means that it is nonvoluntary, which means it is not “qualified,” which means it does not qualify for the tips deduction.

So ... how is one to know how much of box 7 is qualified?

Fortunately – and given that the law was passed halfway into the year – the IRS realized that employers and payroll companies could not make these changes retroactively. In Notice 2025-62, the IRS stated that - for 2025 only - an employee can assume that Box 7 is the same amount as qualified tips. Employers can also get this information to employees via other means, such as an online portal.

A new W-2 will be in place for 2026.

What about tipped self-employeds?

Now we are circling back to my situation and the tips deduction.

Scratch that Form W-2, as I will not be an employee. I may get some flavor of Form 1099, though.

Form 1099-K used for credit and debit cards

Form 1099-NEC used for independent contractor

Form 1099-MISC used for other reportable payments

I took a look: nope, not seeing any 2025 reporting for tips. I see something on Form 1099-MISC Box 10 for payments to an attorney, but I am not an attorney. The IRS has said, however, that they are revising the 2026 forms to include tips information. That's OK, I will adjust my 2026 invoices as necessary - if I can otherwise qualify for the deduction.

I gotta ask: how will the IRS know if I am self-employed and have 2025 income representing qualified tips?

I see the following IRS guidance: “you can rely on your own tip records.”

Not the hardest tax planning I have seen.

The IRS buttressed this with proposed Regulations on September 22, 2025.

I see four requirements in the Regulations for a qualified tip:

· Is paid voluntarily

· Is not received in a specified trade or business

· Satisfies other requirements established by the Secretary

· Received in an occupation that customarily and regularly received tips on or before December 31, 2024

Let’s see:

· I can meet this: you can pay me voluntarily or involuntarily, but you will pay me.

· This is a problem. I am not going to labor you with the provenance and metaphysics of “specified trades or businesses,” other than to say that common examples include physicians, attorneys, and accountants.

o But there is transitional relief until January 1 “of the first calendar year following the issuance of final regulations ….”

§ I may still be in the running.

· I will worry about other requirements when they happen.

· We hit a hard stop with “customarily and regularly received tips.”

o The IRS published a list of qualifying occupations.

o I see the expected: bartenders, wait staff, hair stylists, and so forth.

o I see a few unexpected: home landscapers, electricians, and plumbers.

o I see nothing for accountants and tax preparers.

o I do see something for “#209 Digital Content Creators.”

§ I suppose I could put these blogs on YouTube and be a “content creator.”

I am not seeing a (reasonable) way to meet that fourth requirement and get my fees to qualify for the tips deduction, unfortunately. I suppose an occasional client might mark my fee as a “tip” – thereby hoping to help me out – but I am not seeing a way to sidestep (at least legitimately) the “customarily and regularly” hurdle.

I won’t, but you know somebody will.

The tax literature is littered with cases like these.