One of the accountants brought me what she considered

an unusual W-2.

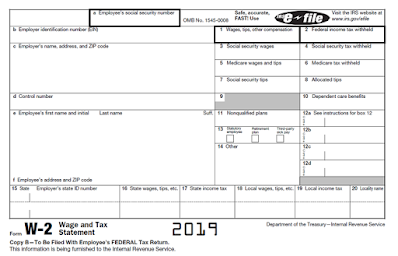

Using accounting slang, Form W-2 box 1 income is the

number you include on your income tax return. Box 3 income is the amount on

which you paid social security tax.

There often is a difference. A common reason is a 401(k) deferral – you

pay social security tax but not income tax on the 401(k) contribution.

She had seen fact pattern that a thousand times. What caught her eye was that the difference between box 1 and box 3 income was much too large to just be a 401(k).

Enter the world of nonqualified deferred compensation.

What is it?

Let’s analyze the term backwards:

· It

is compensation, meaning that there is (or was) an employment relationship.

· There

is a lag in the payment. It might be that the employee wants the lag; it might

be that the employer wants the lag. A common example of the latter is a

handcuff: the employee gets a bonus for remaining with the company a while.

· The arrangement does not meet the requirements

of standardized deferred compensation plans, such as a profit-sharing or 401(k)

plan. You have one of those and tax Code requires to you include certain things

and exclude others. That standardization is what makes the plan “qualified.”

A common type of nonqual (yep, that is what we call

it) is a SERP – supplemental executive retirement plan. Get to be a big cheese

at a big company (think Proctor & Gamble or FedEx) and you probably have a

SERP as part of your compensation package.

I wish I had those problems. Not a big company. Not a

big cheese.

Let’s give our mister big cheese a name: Gouda.

Gouda has a nonqual.

The taxation of a nonqual is a bit nonintuitive: the FICA

taxation does not necessarily coincide with its income taxation.

Let’s run through an example. Gouda has a SERP. It

vests at one point in time- say 5 years from now. It will not however be paid

until Gouda retires or otherwise separates from service.

Unless something goes horribly wrong. Gouda does not

have income tax until he receives the money. That might be 5 years from now or

it might be 20 years.

Makes sense.

The FICA tax is based on a different trigger: when

does Gouda have a right to the money?

Think of it like this: when can Gouda sue if the

company fails to pay him? That is the moment Gouda “vests” in the SERP. He has

a right to the money and – barring the exceptional – he cannot be stripped of this

right.

In our example, Gouda vests in 5 years.

Gouda will pay social security and Medicare (that is,

FICA) tax in 5 years.

It is what sets up the weird-looking Form W-2. Let’s

say the deferred compensation is $100 grand. The accountant is looking at a W-2

where box 3 income is (at least) $100 grand higher than box 1 income (remember:

box 1 is income tax and Gouda will not pay income tax until gets the money).

There is even a name for this accounting: the “Special

Timing Rule.”

Why does this rule exist?

You know why: the government wants its money - at

least some of it.

But if you think about it, the special timing rule can

be beneficial to the employee. Say that Gouda is drawing a nice paycheck: $400

grand. The social security wage base for 2020 is $137,700. Gouda is way past

paying the full-boat 7.65% FICA tax. He is paying only the Medicare portion of

the FICA - which is 1.45%. If the IRS waited until he retired, odds are the

Gouda would not be working and would therefore have to pay the full-boat 7.65%

(up to the wage limit, whatever that amount is at the time).

Can Gouda get stiffed by the special timing rule?

Oh yes.

Let’s look at the Koopman v United States case.

Mr Koopman retired from United Airlines in 2001. He

paid FICA tax (pursuant to the special timing rule) on approximately $415 grand.

In 2002 United Airlines filed for bankruptcy.

It took a few years to shake out, but Mr Koopman

finally received approximately $248 grand of what United had promised him.

This being a tax blog, you know there is a tax hook

somewhere in there.

Mr Koopman wanted the excess FICA he had paid. He paid

FICA on $415 grand but received only $248 grand.

In 2007 Koopman filed a refund claim for that excess

FICA.

Does he have a chance?

Mr Koopman lost, but he did not lose because of the general

rule or special rule or any of that. He lost for the most basic of tax reasons:

one only has 3 years (usually) to amend a return and request a refund. He filed

his refund request in 2007 – much more than 3 years after his withholdings in

2001.

Is there something Koopman could have done?

Yes, but he still could not wait until 2007. He would

have had to do it by 2004 – the magic three years.

What could he have done?

File a protective refund claim.

I do not believe we have talked before about protective

claims. It is a specialized technique, and an accountant can go a career and

never file one.

I believe we have a near-future blog topic here. Let

me see if I can find a case involving protective claims that you might want to

read and I would want to write.

No comments:

Post a Comment